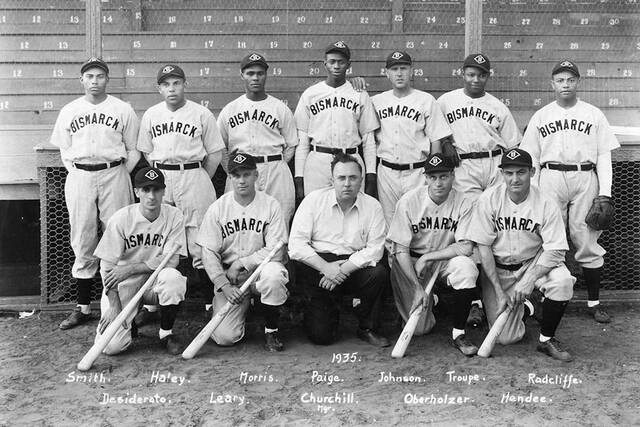

Bismarck’s 1935 national semi-pro championship team, the first integrated team to win a national baseball championship. Kneeling left to right are Joe Desiderato, Al Leary, Neil Churchill, Dan Oberholzer, and Ed Hendee. Standing left to right are Hilton Smith, Red Haley, Barney Morris, Satchel Paige, Moose Johnson, Quincy Troupe, and Double Duty Radcliffe. (Photo provided by UND Today)

February is Black History Month. In North Dakota, the African American population has grown, though historically the numbers were few. But there have been African Americans in the state as long as there have been white people. Early records indicate that the earliest came as slaves of explorers and traders. In fact, the first non-Native born here was African American.

Aside from slaves, others came of their own accord to follow the American dream. One of our most famous North Dakotans was Era Bell Thompson, who became the international editor of Ebony Magazine. She was the daughter of a homesteader near Driscoll who then moved to Bismarck in 1919 to run a secondhand store.

Ironically, Blacks had a major advantage over the Scandinavians and the Germans — they spoke English. Some were associated with the steamboat trade from St. Louis, but many came as soldiers. They had fought in the Civil War, serving in regiments that later came out west to provide protection for railroads, homesteaders and gold-seekers.

In July 1891, two companies of African Americans from the 25th Infantry Regiment arrived at Fort Buford on the upper Missouri, quickly followed by a third. The next summer, two companies from the 10th Cavalry joined them, and by 1893, Fort Buford was made up entirely of Black enlisted men; the only whites at the fort were commissioned officers. Native Americans called them “Buffalo Soldiers” because their hair reminded them of curly buffalo hair.

There were also African Americans working as cowboys. Twenty-two-year-old James Williams worked cattle in the Medora area in 1886, and it’s said that he was such a good roper that he once lassoed a goose right out of midair. Another well-known Black cowboy was John Tyler, a friend to Teddy Roosevelt.

Of those who came to homestead, William Montgomery is noted for his 1000-acre bonanza farm south of Fargo. In the Mouse River area, Frank Taylor was a highly respected horse dealer; he had a ranch near Towner where he specialized in raising and trading Percherons and Belgians.

In sports, North Dakota had integrated baseball teams in the 1930s, long before Jackie Robinson broke into the majors. Baseball teams across North Dakota lured some of the best players in the world from the Negro Leagues.

The most famous interracial team to participate in North Dakota was the Bismarck team of 1935, which included such famous African-American baseball players as Quincy Troupe, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Hilton Smith, and legendary pitcher Leroy “Satchel” Paige.

However, Blacks in North Dakota still had to contend with prejudice, discrimination and racism. experienced in various forms, some subtle, others more glaring. Paige, one of the most famous baseball players of the day, dealt with it when looking for a house to rent while he played for the Bismarck semipro team in 1935. Despite being the team’s ace pitcher and most valuable player, he was unable to find a suitable house or apartment for rent, as landlords would claim that the properties had already been rented. Later, Paige would pass the homes and find them still empty. Paige and his wife finally were forced to rent a refurbished railroad freight car formerly used as a bunk car for work gangs.

While African Americans may not have settled in North Dakota in large numbers, their contributions remained noteworthy.

Material from the 1993 thesis “African Americans in North Dakota, 1800-1940” by graduate student Stephanie Abbott Roper for her UND master’s degree, was added to this article.